Bright lights and a bidet chandelier: Iran gets a blast of shocking colour

ow will British ‘colour activist’ David Batchelor go down in a country where vibrant hues are all but banned? Will his lavatorial light land him in trouble? redlinepowdercoating.com

In the early 1990s, visitors to Iran would have been struck by the country’s lack of vibrant colour. Eight years of war, on top of a revolutionary ideology that regarded individual expression as frivolous, had obliterated it from the streets. The palette of the public space was dominated by dark shades of brown, grey and navy blue, interspersed with the prominent black chadors of the women.

In most religions, white is the colour of purity, cleanliness and virtue. But in Iran, it was black that symbolised righteousness. This was especially ironic given that, before the revolution, devout Iranian women would wear light, flowery chadors to step out of their homes. Where did the colour go in Iran? And where did black come from?

These questions motivated my own staged photographs of unusually colourful chadors in 2005, as I sought to investigate the demise of the flowery ones worn by my aunt and grandmother as I was growing up in pre-revolution Iran.

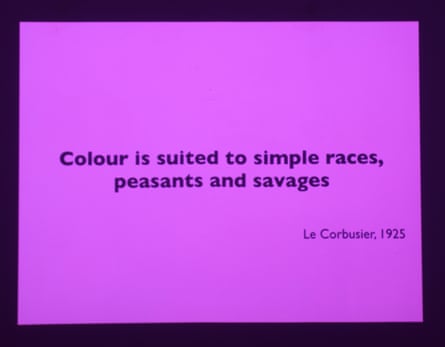

I found some answers in David Batchelor’s book Chromophobia, in which the British artist traces the trajectory of highbrow hostility to colour in western thought. Colour, he writes, is regarded either as the “property of some foreign body, usually the feminine, the oriental, the primitive, the infantile, the vulgar, the queer or the pathological … or relegated to the superficial, the supplementary, the inessential or the cosmetic”.

Take out the oriental and the primitive and this could easily be a manifesto for revolutionary Islamic Iran in its early years, where the only colour in the country was found in the murals memorialising revolutionary heroes and martyrs of the war with neighbouring Iraq.

So I was thrilled to hear about Batchelor’s solo show in Tehran’s Ab-Anbar Gallery, a stone’s throw from Revolution Avenue. Spanning the past 20 years, 120 works offer Tehranis a taste of his fascination with colour. First, there were what he calls his doodles: an installation of 90 drawings, creating a wild collage of colours.

In a room opposite, Batchelor’s “poured” paintings show how the doodles develop into larger pieces. Between these and his glowsticks – digitally tuned colour LEDs held in geometric steel frames – he plays around with rigid ideas of two and three dimensions. His paintings all include a black rectangle at the bottom channelling a plinth, while his light installations are hung flat to be looked at as canvasses.